Capacity markets are used in some wholesale electricity markets to pay resources for being available to meet peak electricity demand. Capacity is not actual electricity, but rather the ability to produce electricity when called upon several years in the future. Capacity market payments cover some or all of the fixed costs of building and maintaining generating resources. In contrast, generators in energy-only electricity markets, like the one used in Texas (the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT)), rely on energy market price spikes during periods of shortage to cover their fixed costs.

Michael Goggin

In the U.S., capacity markets are used by grid operators in New England, New York, and the PJM region that covers much of the Mid-Atlantic and Great Lakes states. In those markets and globally, experts are debating the role of capacity markets as the generation mix evolves to larger amounts of renewable and storage resources.

I recently co-authored a paper arguing that capacity markets are falling short for the reasons outlined below. Energy-only markets, when combined with long-term bilateral contracts to hedge market participants against price risks, can increase flexibility by sending stronger price signals to resources to increase or decrease output when needed. A compromise could be giving states, instead of the grid operator, more authority over resource adequacy decisions, per the model in the Southwest Power Pool region.

Capacity markets drive excess capacity

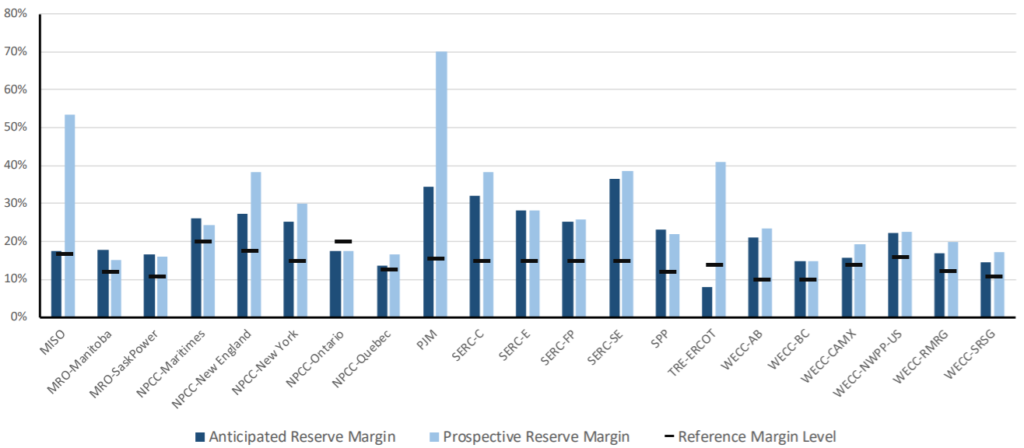

Data from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC) show that the three U.S. regions with capacity markets have some of the largest surpluses of generating capacity, as shown below. Over the next five years, New England’s reserve margin is projected to be 27% at its lowest possible point, and it could be as high as 40%, relative to a target of 17.8%. New York’s reserve margin is expected to be as low as 23% and as high as 30%, relative to a target of 15%. PJM is projected to have a 34% reserve margin at minimum, and it could be as high as 70% if new generation comes online as expected, relative to a target of 15.7%.

One might argue that large reserves of generating capacity are worthwhile to improve electric reliability. However, PJM’s own analysis shows rapidly diminishing marginal returns from reserve margins in excess of 20%. Brattle Group analysis found that the economically optimal reserve margin in the ERCOT region is less than 10%.

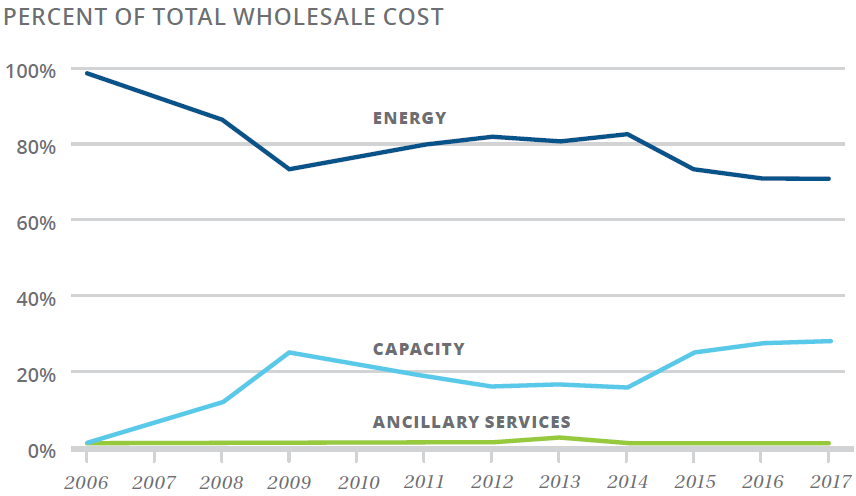

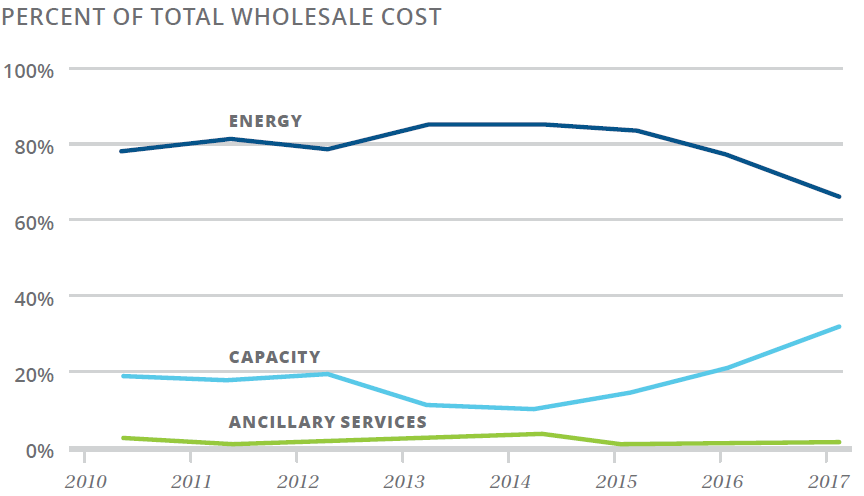

The following charts show that capacity market payments have grown to account for an increasingly large share of total wholesale electricity costs in PJM (left) and New England (right), despite large surpluses of capacity in both regions. At a total cost of $10.3 billion in 2018, the PJM capacity market comprises more than 20% of the cost of wholesale electricity in the region.

Why are regions with capacity markets more prone to surpluses of capacity? Capacity market design decisions driven by self-interested grid operator stakeholders are a key factor. Grid operators themselves tend to be biased towards having more capacity. A shortage event in which energy market prices spike or there is a reliability risk poses a greater institutional threat than the less noticeable cost of supporting excess capacity in all hours of the year. Stakeholders who own generation or have affiliates that own generation are also highly influential in grid operator decisions, and they generally support higher capacity market prices for self-interested reasons.

Recent PJM capacity market design decisions will drive further oversupply by excluding renewable and storage resources

In December 2019, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) imposed a Minimum Offer Price Rule for PJM’s next capacity market auction. For nuclear and renewable resources that benefit from state policy, this rule sets a minimum price that they can offer into the capacity market, which makes it more difficult to clear the capacity market and receive payment. Removing those resources increases capacity market prices, and consumers must then pay for capacity that is redundant with the capacity those resources are providing but for which they are not receiving credit.

Other PJM capacity market rules already undercount renewable and storage resources’ capacity value. PJM requires storage resources to be able to discharge for at least 10 hours to qualify as capacity resources, which prevents battery resources from receiving credit for the capacity they are providing. PJM counts resources’ capacity contribution based on what they can provide across the entire year, even though solar and some demand response resources provide more capacity during summer peak demand periods, while wind provides more capacity during winter peak demand periods.

Capacity market prices are also highly uncertain and volatile, which makes financiers less willing to give full credit for expected capacity market revenues. This provides an inherent bias against capital-intensive renewable and storage resources and towards fossil-fueled resources that have lower capital costs to finance, but larger ongoing costs.

Capacity markets can make the power system less flexible

Capacity markets do not distinguish between the inflexible capacity provided by a nuclear plant versus that provided by a highly flexible battery or gas generator. As a result, capacity market payments can prop up old inflexible generators that are unable to compete on a power system that demands increasing flexibility. Our analysis indicates that around 18,000 MW of coal capacity in the PJM region would be uneconomic but for capacity market payments.

By dulling energy market price signals through creating an oversupply of generating capacity, capacity markets impair the transition to a more flexible power system. In the Texas energy-only market last summer, energy market prices went as high as $9,000/MWh for short periods of time during shortage events, which sends a strong signal for resources to perform when needed. Due to its surplus of capacity, PJM energy market prices were routinely below $50/MWh during peak demand periods.

A better way forward

While the Texas model of an energy-only market with long-term bilateral contracts offers a number of advantages, less extreme solutions also offer significant improvements over the capacity market status quo. Following FERC’s recent imposition of a Minimum Offer Price Rule in PJM, some states are exploring using a provision called Fixed Resource Requirement to effectively opt out of the capacity market.

Returning resource adequacy authority to states is consistent with the traditional divide between state and federal authority, and does not penalize states that want to invest in clean energy resources. State officials are better positioned to oppose the billions in costs associated with maintaining excess generating capacity. Some regions are looking to the Southwest Power Pool model in which the grid operator runs a centralized energy and ancillary services market, but resource adequacy decisions are left to state regulators.

Michael Goggin

Vice President

Grid Strategies

An excellent, well reasoned summary of the issues associated with the existing capacity market in many regions. It is getting clearer that power system flexibility is essential to maintain grid reliability in the presence of high level of VREs. Is there a way to encourage the market construct to value that flexibility more explicitly as opposed to the traditional capacity construct?

Thanks Mahesh! I think the price signals that inherently incentivize performance in real-time energy and ancillary services markets when flexibility is needed are the most elegant way to drive that transition. The ERCOT energy-only model seems to be meeting reliability needs and is allowing innovative resources to participate in driving its resource mix towards greater flexibility as the penetration of variable resources increases.

In theory one could create a forward capacity market that procures flexibility capability and includes performance requirements, like California has attempted with its Flexible Resource Adequacy Criteria and Must Offer Obligation (FRACMOO) construct. Their experience has shown that is quite administratively complex: one needs to specify the types and quantities of flexibility that are needed (how fast, for what duration, etc.), the penalty/reward structure to drive performance, and how those incentives are aligned with the energy and ancillary services markets. If designed well, it seems like the best possible outcome is an incentive structure that mimics the incentives inherently provided by real-time energy and ancillary services markets; at worst, the rules will be written based on the characteristics of existing resources (gas combustion turbines) and not fully reward or even exclude innovative resources like demand response, energy storage, and curtailed renewables that can provide superior service. I think the market, with oversight from state regulators, is better suited to make those complex and uncertain decisions than an RTO stakeholder process.

This is a great post illustrating the fallacies of capacity markets. Yet they live on even in ‘advanced’ countries. Is it safe to say that all non-capacity market resources are indirectly subsidizing capacity market generators through the lost revenue from suppressed prices? Can vertically integrated utilities rate-case old fossil assets participating in capacity markets that would otherwise be unviable in a competitive electric energy market?

The SPP & ERCOT models start to look good.

Don’t Texans wish they’ve had a robust capacity markets now?

It was definitely interesting to circle back on this article post the Texas Freeze.

“Capacity markets drive excess capacity” so where excess capacity already exist how should it be managed for the generators to recover their investment.

Nicholas, Exactly. The problem with ERCOT’s price only model during Texas Freeze such as Winter Storm Uri,is a natural gas generating plant cannot offer power at any price, if it does not have fuel because the natural gas wells and pipelines are frozen. A capacity market would force the generators to go up stream and seek bids for firm service that matches that of the criteria on the Capacity Market RFP. No generator can enter into such firm upstream commitments based on some unknown scarcity price at some unknown time in the future if and when it occurs.